We finally released the bees in early July! They emerged immediately from their cocoons but we quickly realised they looked rather unhappy in the cages. They clustered around the top corners in a way that suggested they wanted to escape (Picture 1).

They did not visit the artificial flowers, nor the nectar we had provided in syringes. It was clear that the cages were a problem.

In the interests of time we decided to leapfrog Plan B (putting potted plants in the cages) and move directly to Plan C – that is, removing the cages and allowing the bees to forage freely in the environment (Picture 2).

We figure that it may be that mason bees need to have an initial foraging/orientation flight before they are able to decide to breed, and we are working on a plan for a future run of the cage experiment where we allow them to breed freely first, then put up the cages with the artificial flowers once the bees are breeding.

As soon as we removed the cages, the bees moved into action! Much happier now, they visited in large numbers the Phacelia (purple tansy) we had planted outside the cages for just this eventuality (Picture 3).

Soon after that we started seeing nesting activity, with pollen balls being deposited and eggs being laid (Picture 4).

Gratifyingly, the bees nested in all our temperature treatments. Curiously they seemed to nest more in our heated treatments (ambient +4 and ambient +8) than in the ambient group. Interestingly, the numbers of bees visiting the Phacelia dropped off substantially once they began breeding, and we think the Phacelia merely provided them with nectar “fuel” and they do not visit them for pollen (this ties in with literature on the bees’ preferences).

Now that we had pollen balls being collected in all treatments, we swung into data collection mode.

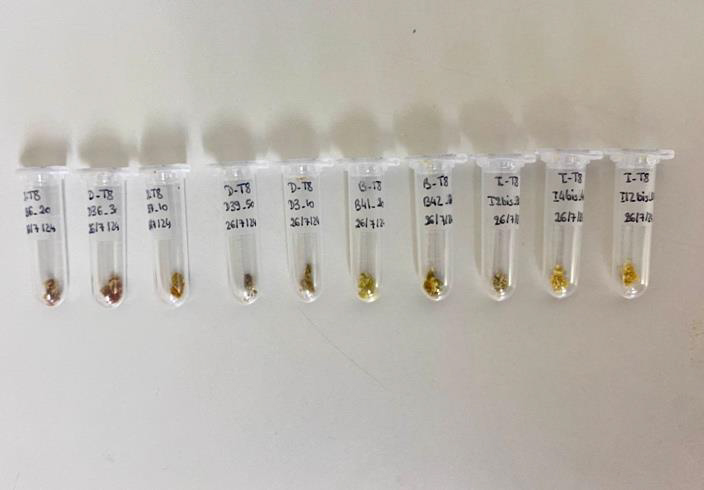

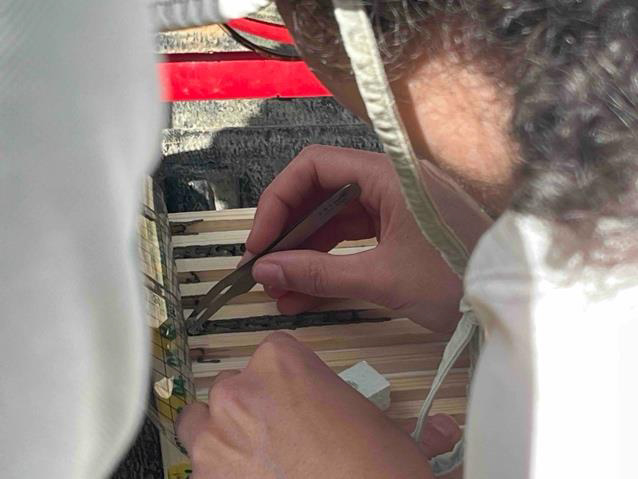

First we remove the wooden nesting blocks from the experimental nests, and recorded the stage of development of each larva. To sample a pollen ball, we extract the larva together with the pollen (Picture 5) and place it in an individual nest. We weigh the pollen ball and take a sample of 10% of its weight which will be split up for analysis of (1) the pollen species present and (2) the nutritional composition (the % protein, fat and carbohydrate).

We’ve now collected hundreds of pollen samples (Picture 6). We will be analysing whether their weight, pollen composition and nutritional content are different among the 3 temperature treatments.